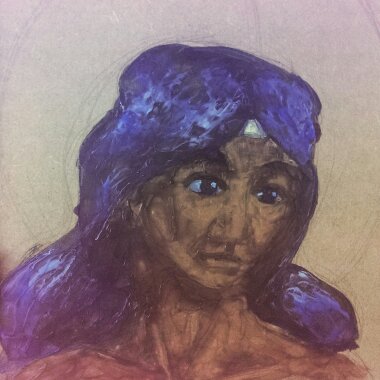

First time doing encaustic painting with bristle brushes.

The painting was on unprimed 12mm MDF with a sketch in medium-soft (B) graphite.

Observations

The brushes didn’t drink the paint the way I expected. I suppose that’s because encaustic has more in common with oil paint than watercolour. It’s been more than ten years since I last used oil, so I was a little worried that I’d be starting from scratch, but I soon got into the swing of it.

Perhaps because I was expecting the brushes to absorb the paint more than they did, the paint went further than I expected. I’ve barely made dent in my supply and I was using it unthinned.

The initial strokes with a loaded brush were quite pleasant. The paint went down well and covered a good amount of the board, the graphite sketch didn’t seem to interfere with the application, and even though the wax cooled rapidly on the brushes, it was easily reactivated on the hot plate.

Unfortunately, some fairly significant issues emerged during the first session.

The quality of the marks left much to be desired: the initial contract with the board often left a blob of paint which rapidly hardened, resulting in a blotchy, uneven tone and surface. Worse than that, new strokes would lift the previous layers, creating bald patches that exposed the board below.

Both problems were very probably caused by me not fusing the paint until after the session.

At the end of the session, I used the heated stylus with a palette knife attachment to fuse the wax and manipulate it. I also used it to apply some opaque colours to add tints to the image, bit that’s very much within the sphere of how I’ve been using encaustic paint up to now.

Once the paint was fused, the quality of the blending and adhesion improved noticeably.

Conclusion

This being a materials test, I didn’t think in necessary to prime the MDF and I think that hindered my ability to assess the medium properly. Due to the colour of the wood and the translucency of the paint, MDF isn’t suited to being used raw and needs to primed before use.

Ultimately, I intend to move on to ‘proper’ wood, birch ply and solid wood blocks, which will all have their own learning curve, but I’ll continue the paint tests on MDF due to its relative affordability.

One thing that this really drove home was the need to fuse paint between layers. I might look into using a blowtorch to minimise disturbing the paint, but I’ll have to be mindful of not singeing the board as MDF releases toxic vapours when burned.

Notes for next time

- Prime the board

- Fuse between layers

Future exploration

- Prime the board using clay paint

- Prime the board using wax

- Prime the board using encaustic gesso (?)

- Try heated palette knives (not the stylus)

- Use a blowtorch for fusing

- Mix with oil paint, oil pastel, MPO

- Try a tonal under-drawing in graphite and/or charcoal

- Include pyrography and graphic elements (not on MDF!)

- More encaustic techniques – etching, filling, inclusions, scraping back, burnishing, impasto, dripping, pouring…