Line drawing

Line drawing is the oldest and most common style of art and, whether the line is drawn, painted, incised or raised, it has been part of art since prehistory. That said, it wasn’t until the renaissance that artists were able to transcend the line into representation of mass (Speed credits Leonardo da Vinci with developing perception sufficiently of overcome the ‘colouring between the lines’ of earlier artists, including masters like Botticelli).

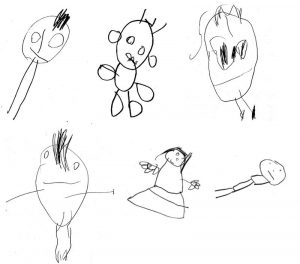

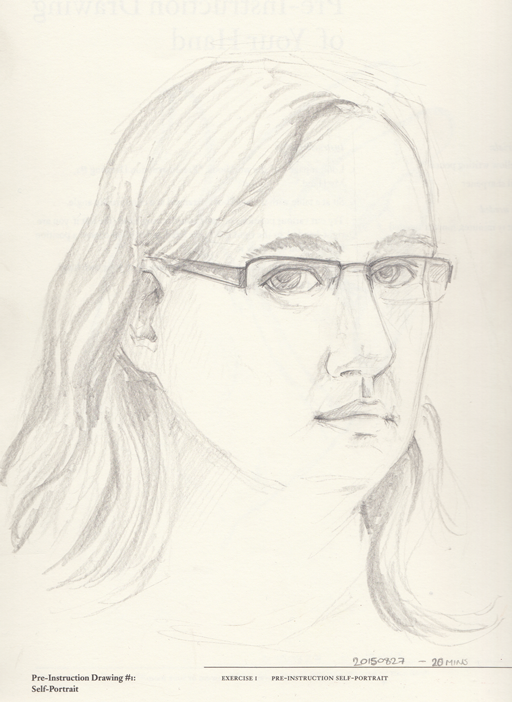

As Speed explained in the last chapter, using line to show the boundaries of mass is the first expression of our understanding of the world, and this is why many beginning artists struggle to depict lost edges and why many pictures that rely heavily on imagination are predominantly line-based.

“Most artists whose work makes a large appeal to the imagination are strong on the value of line. Blake, whose visual knowledge was such a negligible quantity, but whose mental perceptions were so magnificent, was always insisting on its value. And his designs are splendid examples of its powerful appeal to the imagination.”

Perhaps this is why many artists who draw from imagination sketch with line, regardless how the choose to render the final piece. Taking a line for a walk allows you to explore an idea in a way that blocking in masses doesn’t permit for.

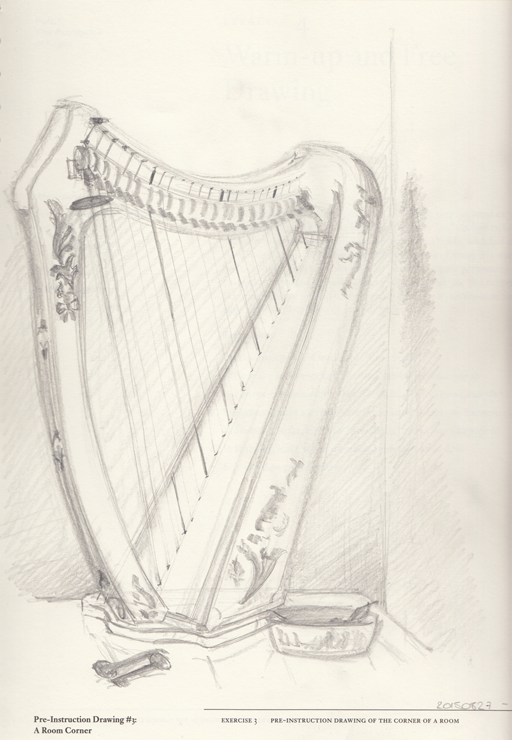

When da Vinci said “the first object of a painter is to make a simple flat surface appear like a relievo, and some of its parts detached from the ground; he who excels all others in that part of the art deserves the most praise,” ‘relief illustration’ was novel and, although the artists of the time were beginning to move away from the outline and colour model, it wasn’t until Velázquez that the idea of a painting being ‘objects in space’ (as opposed to images of a plane) was challenged or vision was used as more than an aid to some mental model.

Here, Speed suggests that art has, in some ways, suffered for the move away from line. In accordance with his theory that line suggests an innocence or primitive quality, he feels that later works lack the freshness of a Botticelli, and highlights one of the dangers of an overly natural approach: that the viewer becomes distracted; looking not at the painting, but at the landscape it represents, applying the same information-gathering thought processes they would if confronted with the scene in real life.

For this reason, the artist must be disciplined in their approach to detail – “the accumulation of the details of visual observation in art is liable eventually to obscure the main idea and disturb the large sense of design on which so much of the imaginative appeal of a work of art depends.”

The key traits of line are simplicity, purity, imagination and design; excessive detail and visual fidelity is a detriment to the benefits of linework.

In Speed’s opinion, the highest pinnacle of art is “when to the primitive strength of early at are agreed the infinite refinements and graces of culture without destroying or weakening the sublimity of the expression”.

In Speed’s opinion, the refinement and graces of culture for painters are an increasingly faithful adherence to the appearance of nature. The height of this refinement was in the mid-nineteenth century and, by the time Speed wrote TPaSoD, he felt that art had become ‘misdirected’ by influences from distant countries and artists’ response to technology (Japanese ukiyo-e prints came to Europe in the 1860s and the daguerreotype camera was released in 1839). Artists, most notably the Impressionists, rebelled against photorealism and argued that it was impossible or undesirable to beat the camera at depicting reality; others, characterised by the Japonism movement, drew on the style and influence of non-Western cultures and began to paint in increasingly stylistic fashions.

I’m not sold on this theory of the decline of art, to be honest. It seems too much like every generation lamenting the decline of the young people of today. Although the early Impressionists don’t do much for me, I see it as the start of painting finding an identity and a purpose once it’s primary function (that of documenting reality) is performed better, faster and cheaper by something else. The start of art’s turbulent teenage years, or it’s mid-life crisis?

Images from Wikimedia Commons.