The Online Manga University study group is reading through Harold Speed’s The Practice and Science of Drawing (first published in 1900). Chapter one, the introduction, is a discussion on ‘what is art?’ and ‘what is the purpose of art?’, with an added comparison on ‘art for art’s sake’ with ‘art for subject’s sake’. A little light reading to get us started, then(!).

Starting off, Speed quotes Ruskin and externalises the artistic impulse into something which acts through the artist. “Not in him, but through him” is a sentiment which comes up again and again whenever people take a philosophical approach to art – the idea that, as artists, we are a conduit for some ineffable creative spirit rather than the source. It’s not a bad idea, nor one I necessarily disagree with, but it has an element of spirituality – of submitting yourself to a higher power – and carries a connotation that whatever is achieved by the artist is not entirely their doing, and I’m inclined to resist that idea. Maybe it’s me being arrogant or idealistic or just a godless heathen, but the idea that I’m a tool operated by an external agent and (perhaps) ultimately not responsible for what I’m moved to create doesn’t sit well with me.

Moving on.

Speed says “[it] is the business of the artist to develop his talent so that it may produce a fit instrument for the expression of whatever it may be given him to express, which is fair enough. Translating a concept to a physical object is a seriously difficult job and I can’t disagree that any artist worth the title should strive to be able to execute the concept (wherever it came from) as faithfully as possible. This means using the best tool for the job, as Speed points out:

Each art has certain emotions belonging to the particular sense perceptions associated with it. There are some that only music can convey[…]; others that only painting, sculpture or architecture can convey […]. In abstract form and colour – that is, form and colour unconnected with natural appearances – there is an emotional power, such as there is in music, the sounds of which have no direct connection with anything in nature but only with that mysterious sense we have, the sense of harmony, beauty or rhythm (all three but different aspects of the same thing).

So, we move from ‘what compels us to create art?’ to ‘why does art appeal to us?’.

Speed quoted Tolstoy at the beginning of the book: “[Art is] an action by means of which one man, having experienced a feeling, intentionally transmits it to others”, although he dismisses it as an inadequate answer to the question ‘what is art?’, I think it’s this intentional transmission of emotion that make art appeal. Art is a very clear, very tangible attempt at communication and music, drawing and painting has the benefit of not being limited by language. Nuance and cultural references might be lost when art is transposed to a different place and time but, if a piece is executed skilfully, it’s a universal language.

Art is the expression of the invisible by means of the visible (Fromentin)

Our experience of things in the world is comprised of more than form and colour – of feelings, emotional response, of connections and correlations and assumptions and inferences – and it’s the job of the artist to explore these feelings, to capture them, and to paint “under the influence of these feelings”.

At this point, Speed introduces the perceived divide between art for art’s sake and art for subject’s sake, and comes down firmly in the middle:

Such deeper feelings are far too intimately associated even with the finer beauties of mere form and colour for the painter to be able to neglect them; no amount of technical knowledge will take the place of feeling, or direct the painter so surely in his selection of what is fine.

Art for art’s sake – “The painter’s concern is with form and colour and paint, and nothing else” – and art for subject’s sake – “Form and colour of appearances are only to be used as a language and give expression to the feeling common to all men” – is a false dichotomy: “Neither position can neglect the other without fatal loss”

The art for art’s sake painter will miss or fail to capture the significance of the subject and descend into arrogance over their mastery of technique while utterly failing to capture the spirit (inner beauty) of the subject, while the art for subject’s sake painter will fail to be convincing, lacking the technical skills required to represent the subject with any accuracy. “The immaterial can only be expressed through the material in art, and the painted symbols of the picture must be very perfect if subtle and elusive meanings are to be conveyed.”

At this point I found myself asking what implications this has for purely abstract art. Are feelings conveyed through entirely non-figurative imagery necessarily more crude because of the broader strokes used? Far from it, argues Speed. With any abstract art, like music, the lack of an identifiable form means that the technical skill of the artist must be exemplary because, without an identifiable subject, the conversation at the heart of the piece relies on the artist’s ability to express emotion through technique.

The expression must be ordered, rhythmic, or whatever word most fitly conveys the idea of these powers, conscious or unconscious, that select and arrange the sensuous material of art, so as to make the most telling impression, by bringing it into relation with our most innate sense of harmony.

Finally we come to Speed’s definition of art: “the rhythmic expression of feeling”, or – alternatively – “the rhythmic expression of life”.

So, then, the measure of an artist is “the quality of their feeling and the fitness of its expression”.

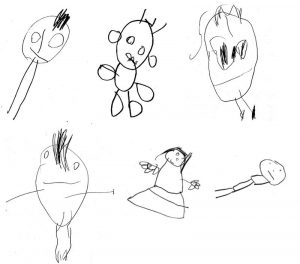

If the artist fails simply recreates what they see with no greater meaning to the work, they’re no better than a mechanical recorder – a camera left running in the woods would do the same job – and galleries would have nothing more to recommend them than holiday snaps. A pretty scene, but not relevant or meaningful unless you were there. Equally, if the artist doesn’t have the skill to express their emotions in an appropriate manner, then they’re basically drawing a smiling face for happiness and a tearful one for sadness with no nuance or room for further emotional engagement

The study, therefore, of the representations of visible nature and of the powers of expression possessed by form and colour is the object of the painter’s training. And a command over this power of representation and expression is absolutely necessary if he is able to be capable of doing anything worthy of his art.